![]()

I expect most macOS, iOS, or tvOS developers to use Xcode as their main development environment, especially if they’re working with Swift. You can use other IDEs with other languages, like Xamarin or Unity for example, but that’s not the “Apple way”. This obviously also applies to anyone working with SpriteKit. In this post, I will detail what’s good or wrong with Xcode support for SpriteKit. And there’s much to say!

As for many file types and other frameworks like SceneKit, Xcode comes preinstalled with some built-in editors for SpriteKit. The goal is to help authoring SpriteKit projects visually, pretty much like you would edit your scenes in the Unity editor for example. Here are some of the most useful.

With the SpriteKit Scene Editor, you can basically build and animate your scenes visually directly from Xcode. I’ve used it for SKTetris and it can be pretty functional. You can add to the scene most of the built-in nodes like sprites, labels, shapes, or even tile maps. Your scenes are then stored in .sks files that you can load directly by name from your app’s bundle.

![]()

It is even possible to setup GameplayKit’s entities and components from the Scene Editor. Each type of node comes with its own custom inspector that allows you to control their look and feel. Animation is another part of the Scene Editor. Indeed, the bottom part of the editor allows you to create custom animations, based on SKAction, for your various nodes. Finally, SpriteKit scenes being nodes themselves, you can easily create isolated scenes for some elements that you want to reuse or load inside another scene. It is also a very good tool to create UI layers for your SceneKit project, as you can use a SpriteKit overlay if needed.

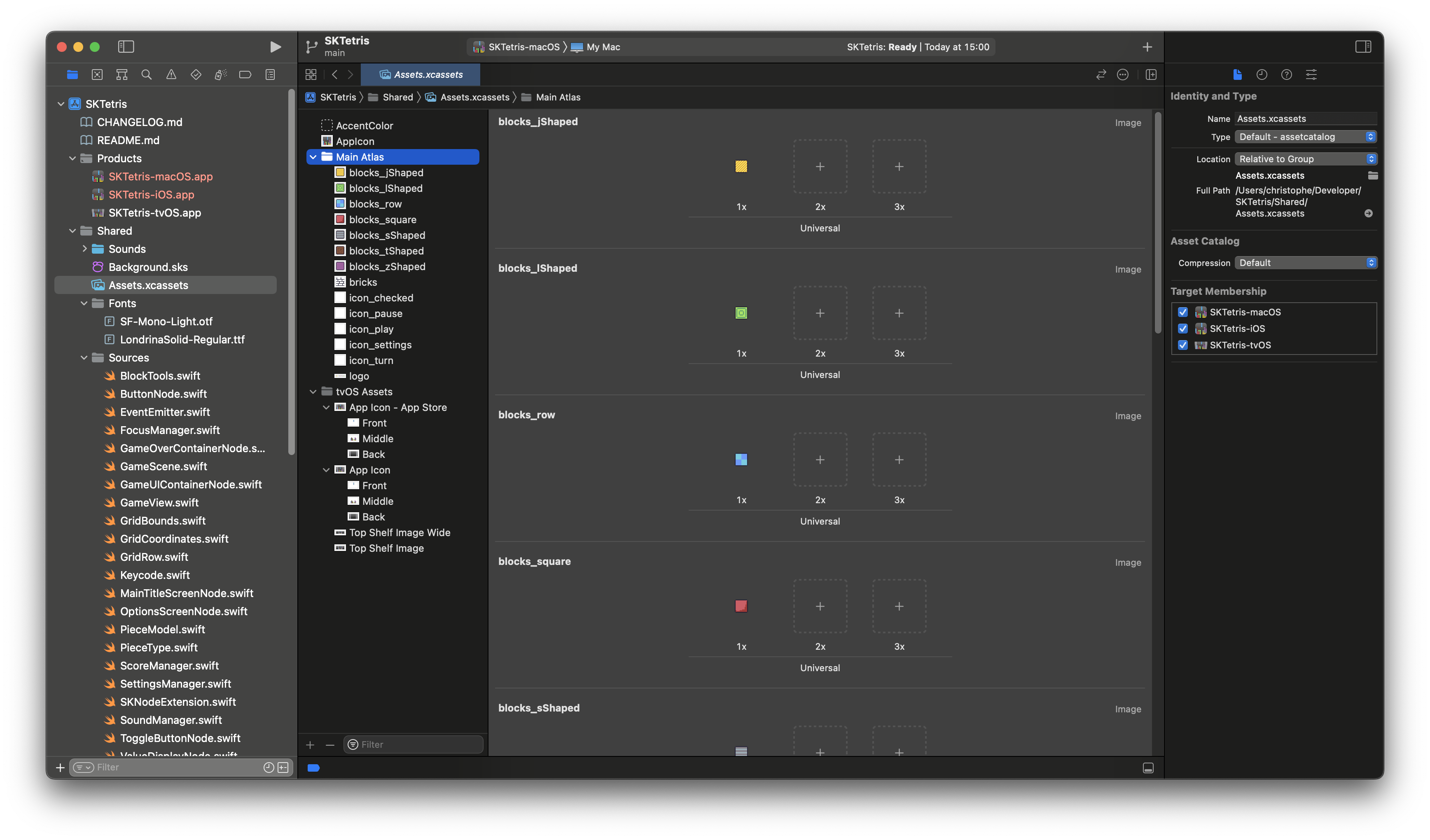

Pretty much no scene would be whole without some sprites, right? That’s where the Asset Catalog may come handy. Indeed, it is the place to store your sprites, individually, or eventually ask Xcode to combine them into atlases for optimum performance. You can even store them in different resolutions for different screen sizes if needed. The Asset Catalog will also handle texture compression or hardware classes (like memory or GPU configurations) to help you provide the most adequate texture to any device in the whole Apple line-up.

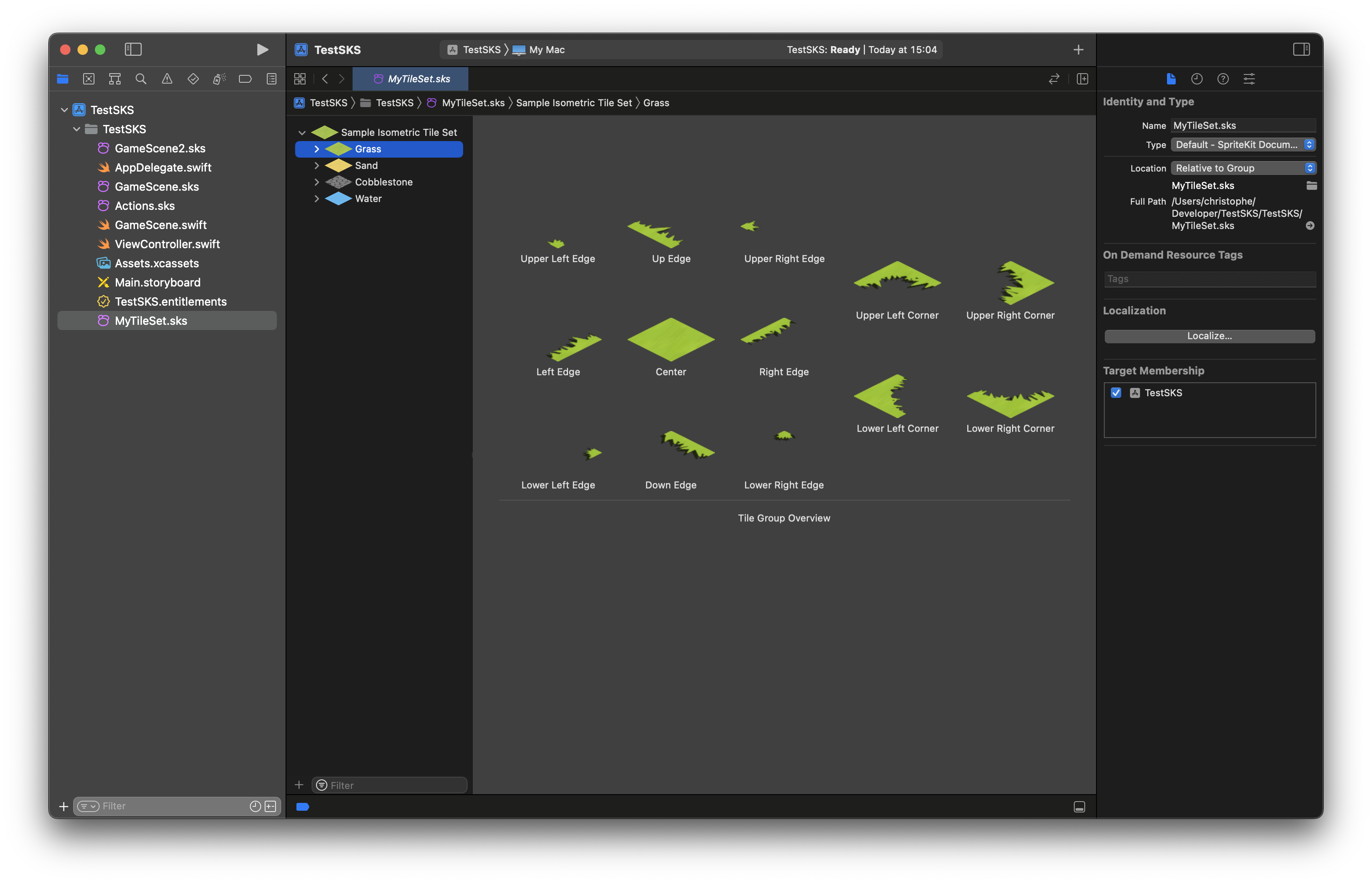

As its name suggests, the TileSet Editor is designed to manage sets of tiles for various map types. You can configure tile groups for complex 2D, isometric, or hexagonal grids. The tile sets, groups and rules are then directly usable in the Scene Editor with a Tile Map node. The TileSet Editor works in tandem with the Asset Catalog as the sprites have to be part of a catalog before being used in tile groups.

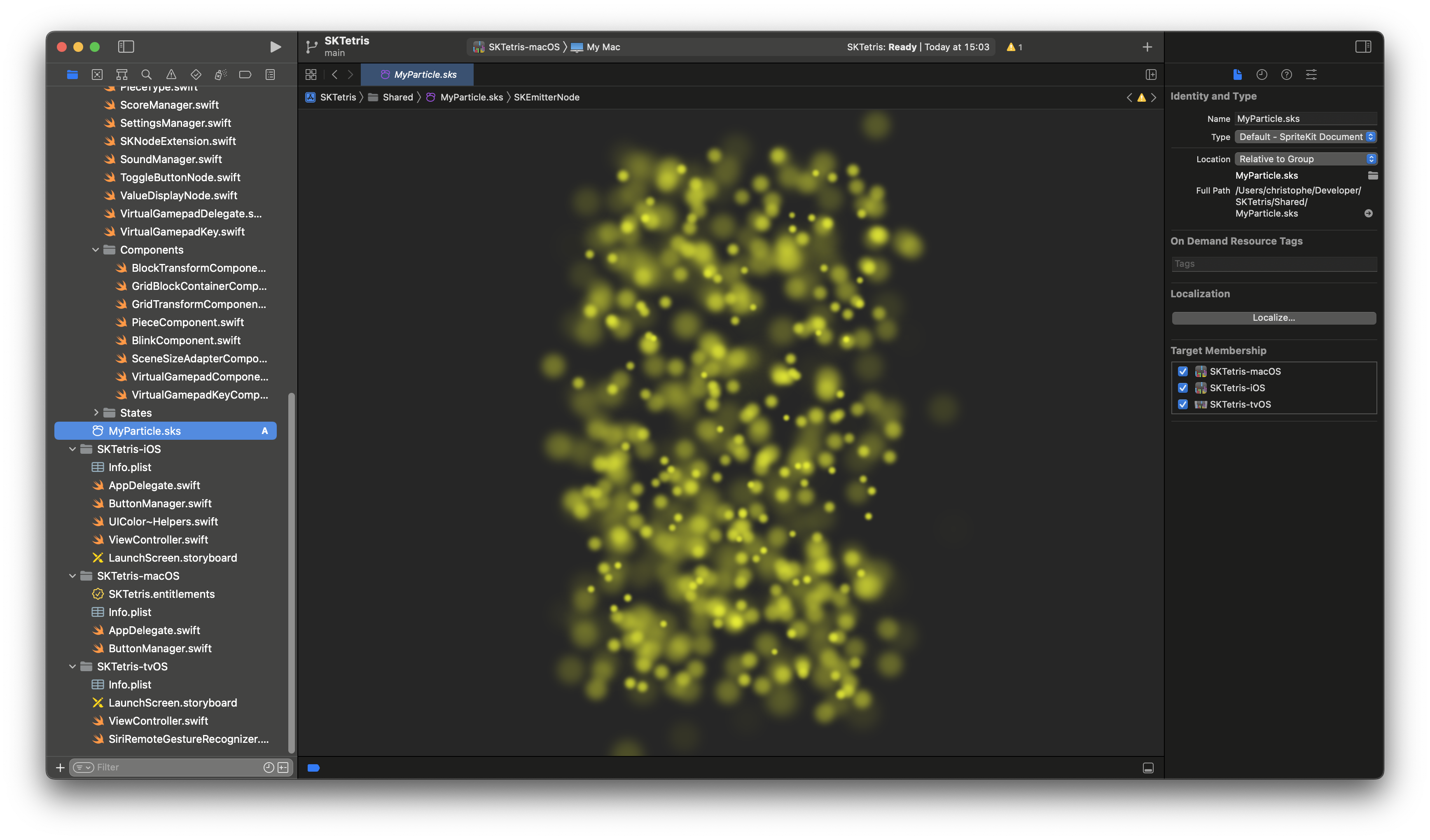

Almost as self-explanatory is the Particle System Editor which helps setting up particle systems visually, that can be then used inside the Scene Editor or programmatically afterwards. Many parameters of the particles can be tweaked, from the lifespan, the speed, the scale, the rotation, or the color over time.

Unfortunately, for almost every good thing Xcode brings to the table, there are drawbacks and inconveniences that make them pretty much unusable in practice.

The Asset Catalogs and TileSets are probably the most valuable assets in everything Xcode has to offer. First, they are properly serialized with JSON files and folders so it is very easy to work with, even in external tools. And the fact that they are humanly readable make resolving conflicts much easier when working with versioning in teams.

However, not everything is perfect. Asset Catalogs notably misses some key parameters like the filtering mode (all textures are created with linear filtering), constraining you to handle nearest filtering mode through code when you use it, notably in pixel art games.

Having more control over the compression format would be great too. Automatic or Lossless is not enough, and allowing access to the wide variety of formats handled by Metal would be nice. For example, 16-bit pixel formats can be very useful to reduce application size without sacrificing quality in many cases.

One last thing is that we have no control over the generated atlases. There is no export of the actual coordinates of the sprites, making almost impossible for additional data layers (normals, emissive, …) to match the exact position for their own sprites.

The Scene Editor is very useful to visualize your scenes. However, don’t try to work in teams on complex scenes (or on particle systems, whose files share the same issues). .sks files are generated as binary files. If two people work on the same file at the same time, you are pretty much out of luck if you have to resolve conflicts. Unless you convert them to XML. Because, under the hood, .sks files are just binary property list files with another name.

With this simple command-line, you can convert them to XML:

plutil -convert xml1 -o my-xml-scene.sks my-binary-scene.sks

I tried a few years ago to convert .sks files to XML to see if Xcode would open them. But at the time, it was immediately crashing. This problem seems now to be resolved as of Xcode 14.2 but if you modify your scene file and save it again, it will fall back to binary. That’s pretty inconvenient. There may be a solution to explore with git’s pre-commit hooks, but Xcode should allow one way or another to keep .sks files as XML files. Even settings the file type as XML in the file inspector doesn’t help.

Another broader issue I have with the SpriteKit Scene Editor is the lack of customization. The editor allows you to assign GameplayKit’s components to nodes in the scene, and you can declare some properties as inspectable that will appear in the user data section (thanks to the @GKInspectable attribute). However, this does not work well for custom types or even enumerations. And you can’t add validators or custom fields like you would in Unity’s custom inspectors.

Both of these issues are huge hits for productivity as they can become regular annoyances or total blockers.

When I started working on CiderKit, I comtemplated my options. But everything mentioned above geared me towards finding custom solutions. Furthermore, the built-in tilemap node for isometric maps is fairly limited compared to what I planed: there’s no elevation support.

Also, even if I still use the Asset Catalogs for storing my textures, atlases themselves are created in an external tool beforehand (at the time directly with Aseprite, but most likely thanks to TexturePacker as the pipeline will mature). Sprites are then generated programmatically based on custom JSON files describing the atlas structure.

Obviously, all of this requires a lot of investment in time and effort to bypass the weaknesses of Xcode’s own implementations. But that also gives me a lot of control regarding data management and optimization, producing way better results in the end.

This is not a surprise that Apple does not invest a lot in SpriteKit in regards to the small community of developers behind it. I am even grateful that SpriteKit has not been deprecated, and I am firmly crossing my fingers it won’t happend anytime soon. But the stack that runs under the hood is very efficient, if not perfect, and we can produce great things with it anyway.

The tools are not everything. The people wielding them are important too.